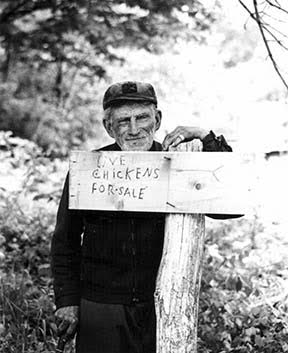

Levi Calhoun Image provided by the Town of Lloyd Historians office Levi Calhoun Image provided by the Town of Lloyd Historians office Greetings from the Lloyd Historical Society! Most of you probably know who Levi Calhoun was, but for newcomers to our Historical Society, here is a story from the About Town archives about him. Happy Thanksgiving to all. Liz Alfonso sat behind a folding card table on the cool October afternoon. Spread before her was a poster with several photocopied newspaper stories and photos, a sheaf of membership forms for the Town of Lloyd Historical Society, and various pens and clips to keep things orderly. “Would you like to join the Lloyd Historical Society?” she asked as I walked up to chat. Liz is even harder to turn down than was her late husband, Danny—a legend in his own time as a champion-seller of raffle tickets for various charitable organizations. As I pulled out my checkbook, I eyed the poster. “We’re also looking for donations to put a proper marker on Levi’s grave…” she said before I had put pen to check. “He’s only got what he hand-carved into his father’s stone, you know.” I looked at the photo of Levi attached to the poster soliciting donations for his headstone. Suddenly, I was five years old standing at the edge of an unpaved Swartekill Road. It was 1949. “Poison ivy,” Levi said knowingly as his clear, light blue eyes surveyed the ravages of the plant’s oil on my arms. There was hardly a photo of me as a child that didn’t portray me scratching a poison ivy rash on some part of my anatomy or covered with calamine lotion. “Stay put,” he said, carefully laying his bicycle on the grass next to our drive. He walked down past the Auchmoody Cemetery into the Great Plutarch Swamp. As he disappeared into the cattails my mother joined me. Levi returned with several stalks of a lush plant—roots, leaves, and flowers. As he walked toward us, he crushed the plant, turning it into a pulpy mass, juice running over his, not exactly manicured, hands. My mother blanched as he proceeded to rub the ooze down each of my outstretched arms. It felt fine. “Jewelweed,” he announced when I was oiled to his satisfaction. Smiling toothlessly, he mounted his bike and was off. My mother was off. In an instant, the jewelweed was off. With water running over my arms, my mother explained it wasn’t the medicine she doubted, just the delivery system. We found a fresh stand of jewelweed, followed Levi’s example, and re-anointed my arms. To this day, calamine lotion is relegated to my “winter” remedy for poison ivy. (You can get poison ivy in the winter. The oil is in the vine, as well as the leaves.) At the memory of Levi’s incredibly aquamarine-blue, smiling eyes, my checking account dipped a little further. My mother said Levi tended beehives near our house and that was why he traveled our road so regularly. It may also have been that he knew where the ginseng grew, or some other American native plant that was paid for handsomely by the ounce. A true naturalist-mountain man, Levi knew his plants, which explains why my mother didn’t throw the baby out with the bathwater, so to speak. But there was so much more to Levi and his lore than just his woodsy culture. When one of his sisters did not come to school for a very long stretch one winter, the truant officer asked Levi where she was. Levi announced the girl had died and was stored up in the barn until the ground thawed. The last time I saw Levi was in 1976. He was clean. Hair, face, hands, clothes. So clean, it took me a moment to recognize him, but then he smiled. He had just come out of the hospital he said. I had heard he was hit by a car while riding his bicycle. We chatted. Parted. “Levi’s died,” my late mother-in-law, historian Bea Wadlin said with gravity. A legend gone. It was spring. April 4, 1976. I thought of his once-stored sister and was glad for him. “There’ll never be another Levi,” Bea said. For sure. But there are plenty of Levi stories, and we keep discovering more. Levi Lore. Born January 20, 1889. Grew up dirt poor or dirt rich, depending on how you think about it. Mutli-siblinged to the tune of 18. As an adult, lived in a bunch of shacks with his goat, dogs, chickens, and whatever. Married once in 1912, but the new wife couldn’t cook, so he took to the bachelor's life. Served in World War I, honorably discharged. Name appears on the soldier’s monument in the Hamlet of Highland. Never had electricity or indoor plumbing or modern transportation. The latter didn’t matter. Levi could run. And did. The late New Paltz historian Peter Harp described one of Levi’s runs in his book, Horse and Buggy Days. “One morning he (Levi) took off,” Harp wrote, “ran to Rosendale, then through High Falls, Stone Ridge, Olive Bridge to Ashokan Reservoir, across the weir, around the north half to the great reservoir, then back home in 8 hours.” Levi lore also recounts his “horsing around.” He would pull a light sulky-type wagon, whinny and neigh and prance, just like a horse in harness. Again from Peter Harp, “At times he would race the trolley, (one ran between New Paltz and Highland until 1925), and due to the many stops the trolley made to take on and discharge passengers, the race would end nearly even.” After Levi’s death, a story in the April 28, 1976, Highland Post tells of Levi’s neighbors and close friends, George Utter and Sue Thomas “…who visited him a few times each week to check on him and as much, to learn from him.” They took Levi to the movies once to see Grizzly Adams. “Levi yelled out right in the middle of the movie,” the Post reported, “‘I know more than he knows, I did that last week.’ He wanted to get up on stage and tell the crowd about living off the land.” Just think what they might have learned. There are stories about his foot races—one even turned up in the New York Times—and stories about his natural cures, and stories about his hermit-like existence, and stories about the wise or funny things he said. But the magic, I believe, of this simple man is that he was like the shuttle, weaving a colorful, warm tapestry of our community. In traveling on his bicycle throughout Highland, Esopus, and New Paltz, he wove us into a more cohesive, more interesting fabric. He gave us a common ground that didn’t threaten or force, require or request, but was simply played out for us to enjoy and share with one another. A year and a half after Levi’s death, Liz handed me a newspaper article from the Poughkeepsie Journal dated November 11, 1997. “Vet can now rest with grave marked in stone,” the headline announced. “Lloyd pays tribute to WWI soldier.” Journal reporter Bond Brungard had interviewed area resident, John Jacobs, about Levi. “Levi asserted to me,” Jacobs said, “that it was OK to be eccentric, that you didn’t have to be a square peg in a round hole, that you can make your own square hole.” About $500 was collected for the $250 headstone. The rest of the funds were to be used to publish some of the Levi stories and to make copies of photos of Levi for the Town of Lloyd historian’s office. Liz said someone is going to organize the Levi stories and we’re going to make a book… “Yes, Liz,” I said, “we are.” I didn’t really know Liz Alfonso well before all this, although our sons played soccer together, and we’ve attended any number of social functions over the years. But now I know something that’s deeply important to her. We share this thread called "Levi." Levi Calhoun’s community grows. Vivian Yess Wadlin

Trustee TOLHPS Update of a story published in About Town a few decades back With thanks to Dot Yess, Liz Alfonso, George Utter, Sue Thomas, Terry Scott, the folks at The Highland Post, Lindsay Sullivan, and all the others to whom Levi’s legacy is important.

2 Comments

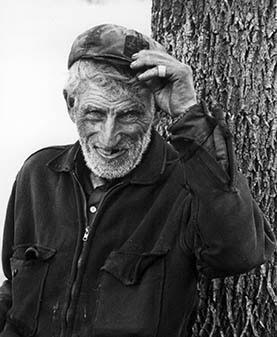

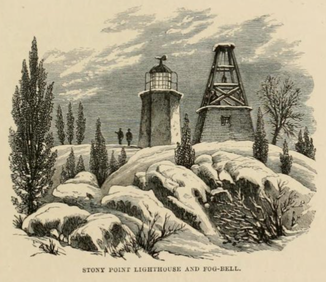

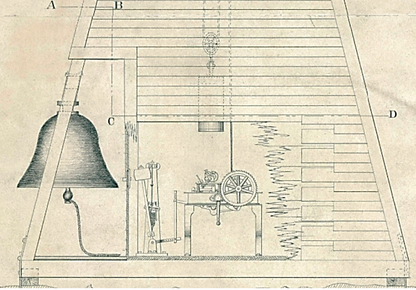

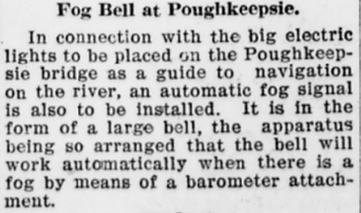

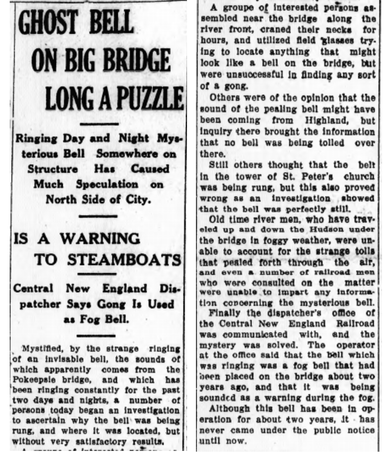

A drawing by Benson Lossing in his book, The Hudson, from the Wilderness to the Sea, published in 1866. A drawing by Benson Lossing in his book, The Hudson, from the Wilderness to the Sea, published in 1866. The completion of the Erie Canal in 1825 increased traffic on the Hudson River dramatically, and the need for navigational aids became obvious. The following year, the first lighthouse on the Hudson River was constructed at the Stony Point Battlefield below the southern border of Orange County. But the light couldn't be seen in the fog, so a wooden fog bell tower was added to the station in 1857. This served until 1876, when the bell was removed from the decayed tower and suspended from a bracket affixed to the lighthouse. A total of 40 lighthouses were built along the Hudson; only 7 of these exist today.  Diagram of an 1872 ringing mechanism Diagram of an 1872 ringing mechanism Ringing the fog bell was not a "one-time" event; foggy conditions could last for days. There are stories of heroes (and heroines) who physically rang the bell for hours, but the demand for an automated mechanism was soon apparent. This is a diagram of an early ringing mechanism (1872). It was wound like a grandfather clock and the falling weight powered a hammer that rang the bell every 20 seconds. Over time, more advanced designs with different powering mechanisms were developed. If you'd like to read more about the various ringing mechanisms, this website has a lot of interesting information, including diagrams and photographs: https://uslhs.org/fog-bells  Kingston Freeman, 11 May 1912 Kingston Freeman, 11 May 1912 A fog bell was installed on the Poughkeepsie Bridge (i.e. the Railroad Bridge). Based on a Light List including Fog Signals, Atlantic and Gulf Coasts, published by the U.S. Department of Commerce in 1931, we know the fog bell on the Poughkeepsie Bridge was located on the east end of the pier, 46 feet above the water. It was on a green platform, on steelwork above the masonry and it was established in 1912. It rang once every 30 seconds and was maintained by the Central New England Railway Co. According to this article, it was activated by a barometer attachment. Apparently the fog bell on the railroad bridge was operational by 1913:  Poughkeepsie Evening Enterprise, 11 Apr 1913, p. 1, col. 4 Poughkeepsie Evening Enterprise, 11 Apr 1913, p. 1, col. 4 The fog bell in Esopus rang throughout the evening of Septemeber 28, 1950. Were the fog bells in Poughkeepsie ringing? This article doesn't say, but it describes the mayhem that occurred when a tug, pulling a string of barges, hit one of the piers of the Poughkeepsie Railroad Bridge. Carleton Mabee, in Bridging the Hudson, writes "Though it was not required in the charter, bridge operators also assisted passing navigators by keeping a fog bell ringing on the bridge. In 1918, this bell was kept ringing by storage batteries which were charged by jars of acid. When the maintenance men replaced the acid in these jars, they poured the spent acid over the edge of the bridge. Inspectors found it difficult to persuade them to stop doing it, even though they explained to them that as they emptied the jars, the wind often blew the acid onto the bridge structure, causing the "rapid deterioration" of the steel." Ferris Davis, a bridge maintenance man when the bell was later powered by an electric cable, remembered the bell as being brass, 18 to 20 inches high. It hung on the pier in the water which was closest to the Poughkeepsie shore, and was loud enough to hear across the river. Another fog bell was part of the new Mid-Hudson Bridge when it was completed in 1930. Based on a Light List including Fog Signals, Atlantic and Gulf Coasts, published by the U.S. Department of Commerce in 1931, the fog bell on the Mid-Hudson Bridge was located on the westerly side of the easterly pier. It was established in 1930 (the year the Mid-Hudson Bridge was completed). It was described as "electric, group of 4 strokes every 15 seconds. Maintained by the State of New York." The fog bell in Esopus rang throughout the evening of September 28, 1950. Were the fog bells in Poughkeepsie ringing? This article doesn't say, but it describes the mayhem that occurred when a tug, pulling a string of barges, hit one of the piers of the Poughkeepsie Railroad Bridge.  Kingston Freeman 24 Apr 1964, p. 6, col. 2 Kingston Freeman 24 Apr 1964, p. 6, col. 2 The fog bell on the Mid-Hudson Bridge was still in operation in 1964, when bids were accepted to recondition the fog bell and its mechanism. By 1976, radar technology had made the fog bell obsolete. The NYS Bridge Authority donated the fog bell from the Mid-Hudson Bridge to the Highland JayCees. Hans and Bob Muhfield used it to make a replica of the Liberty Bell which was featured in the Bicentennial Memorial Day Parade. Bob has recently donated the bell to the Town of Lloyd.

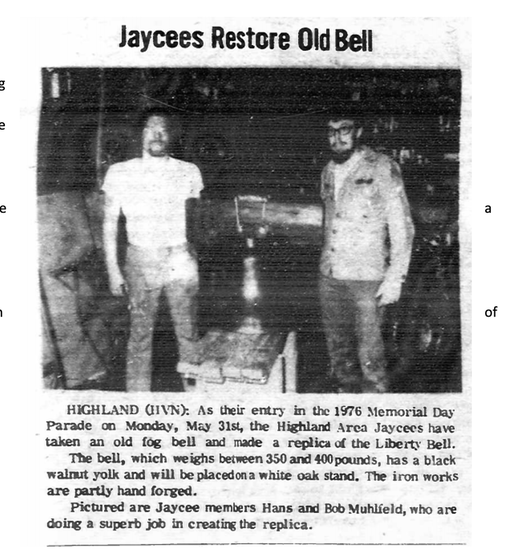

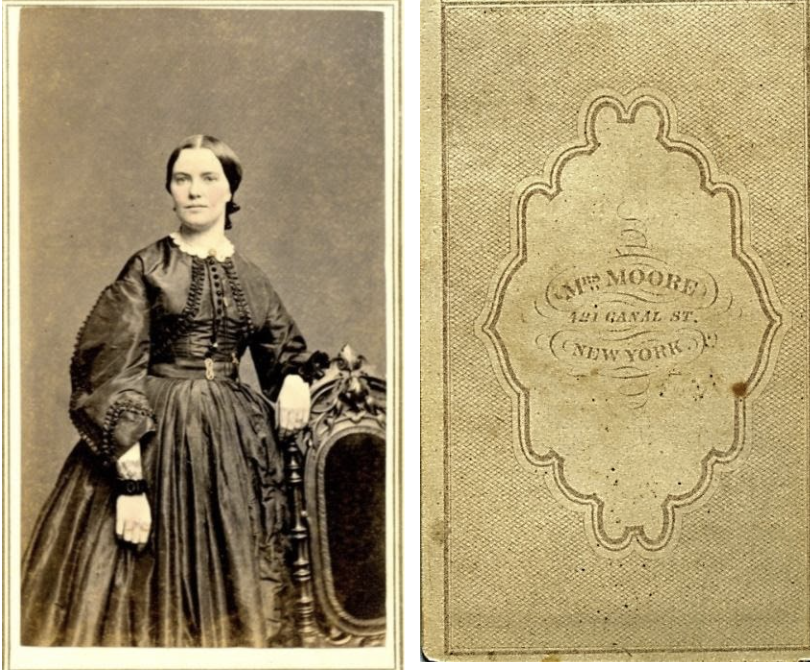

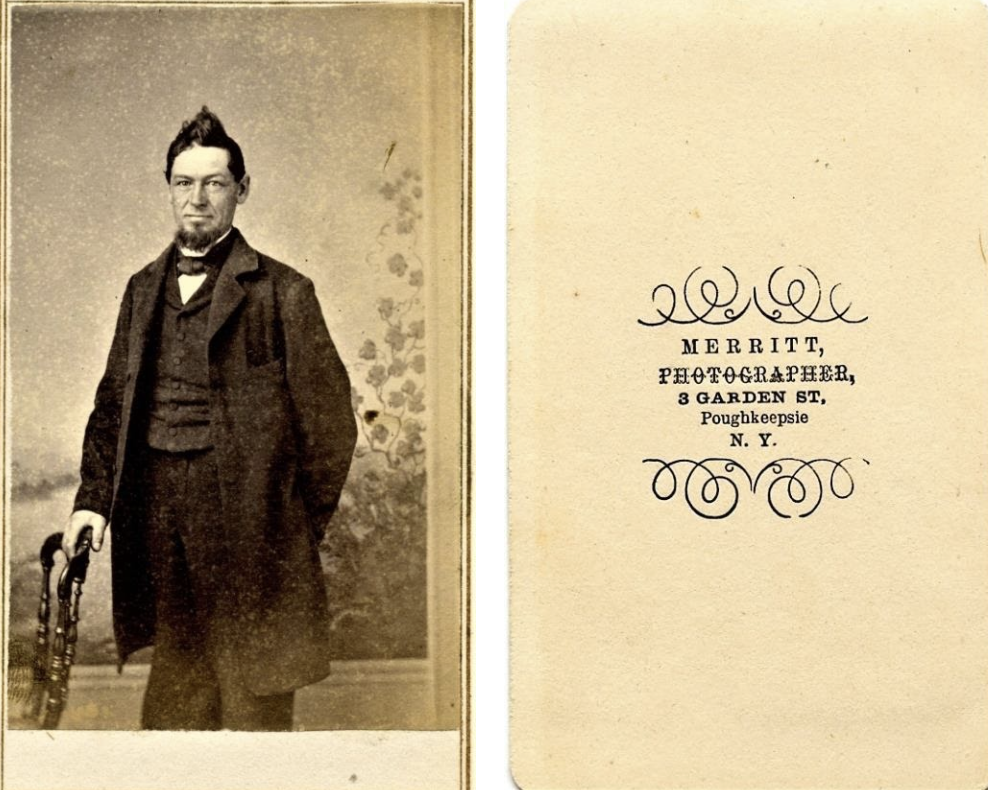

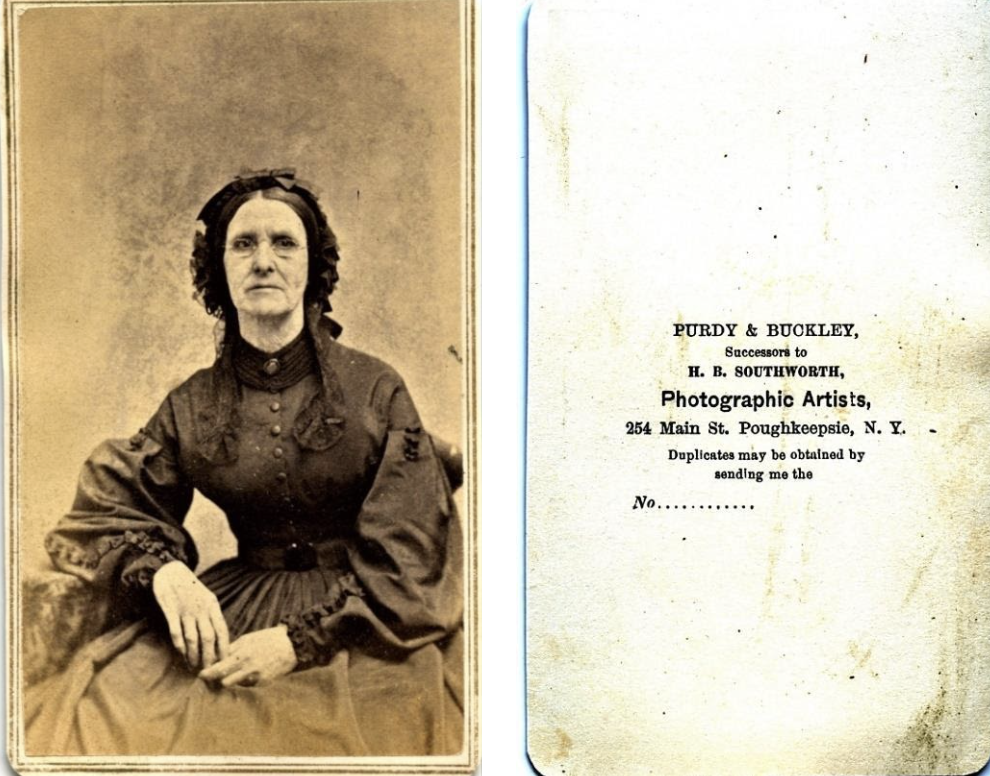

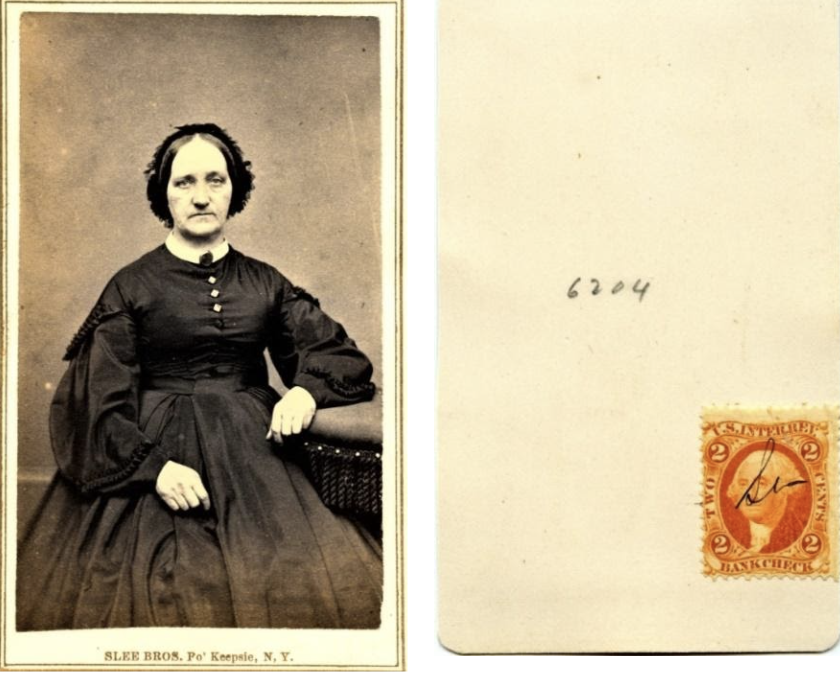

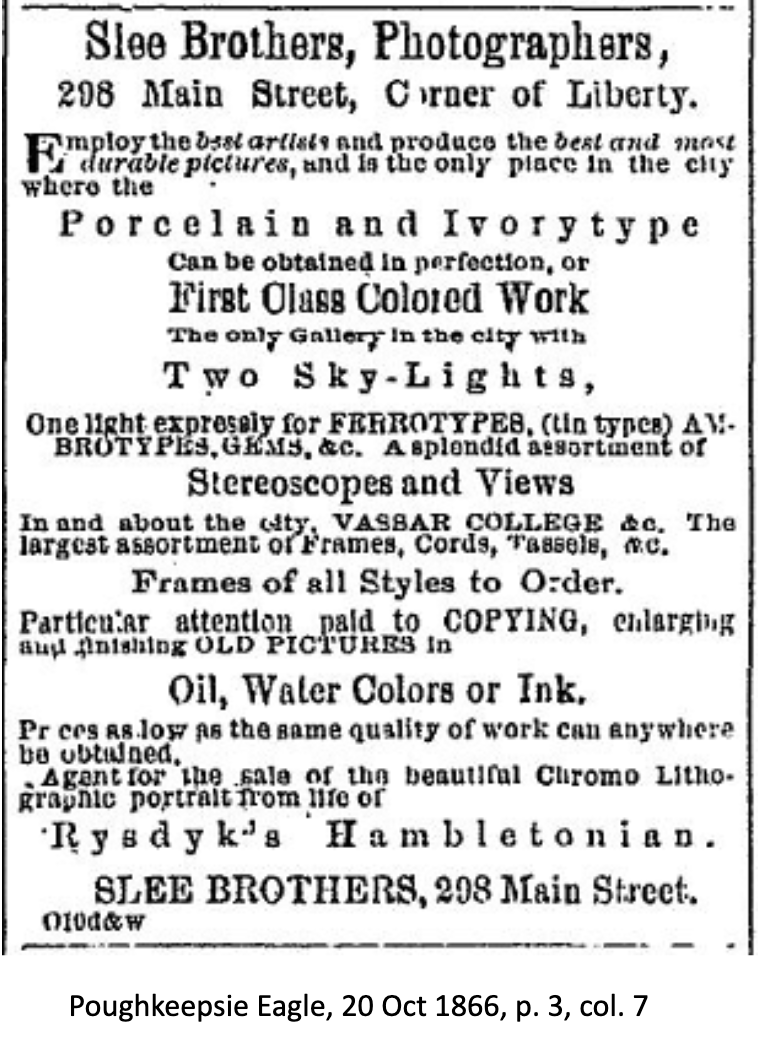

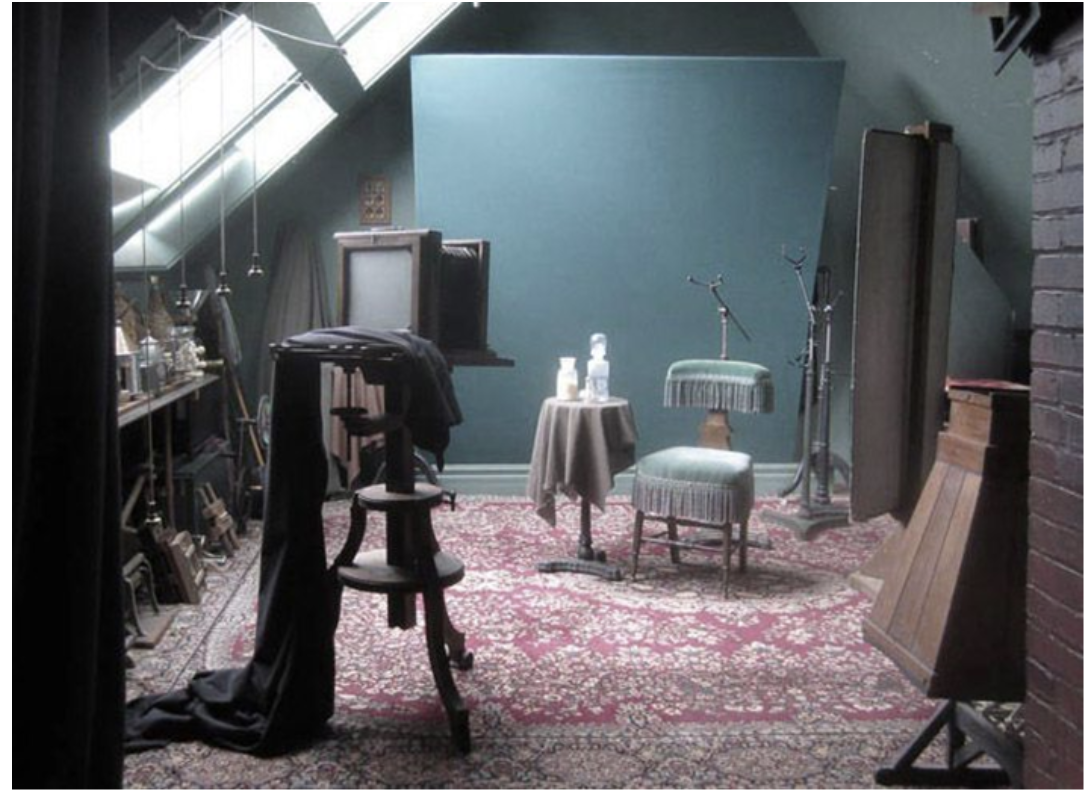

Watch for an update on the future of this bell. Town of Lloyd Historian Joan de Vries Kelley What did our ancestors look like? Before the advent of photograph, the only images that survive are portraits of those who could afford to be painted by a professional artist. That changed in 1839, when Louis Daguerre introduced the daguerreotype which allowed an image to be produced on a silver coated copper sheet.Technology advanced with glass plate negatives (ambrotypes) and in 1856, tintypes ferrotypes). Paper images appeared in 1860 and carte du vistas, photographs the size of a visiting card (2.5" x 4"), became popular. Carte du vistas were collected in special albums which were proudly displayed in Victorian parlors. The Town Historian's collection includes a beautiful album of Elting family carte du Vista (CdV). Someone has thoughtfully recorded the names of some of the people in this album (that is not always One of the CdVs in this album is a photograph of Sarah Elizabeth Dobbs was taken by Mrs. Moore, a young woman from Prussia who had a studio on Canal St in New York city in the 1860s. Yards of silk must have gone into the making of this dress. Many of the photographs were taken by photographers in their Poughkeepsie Studios. Ezekiel J. Elting had his photograph taken by C. Merritt, a Photographer working on Garden St. in Poughkeepsie (no that’s not hat hair…his look is quite stylish for the time) The background for the photograph is a painted mural. The names of photographers are helpful in dating photographs. Imagine traveling on the ferry across the Hudson to Poughkeepsie in this voluminous dress to attend an opera at the Bardavon or have your photo taken. The photographs record how people looked and dressed in Highland during the Civil War Era. Girls always had their hair parted in the center and boys had their hair parted on the side. Boys wore dresses until they were 5 or 6, when they “graduated” to pants. So this is a photograph of a young boy, about three or four years old, dressed in his best outfit. Revenue stamps can be used to identify the dates of some of these photos. These stamps , required from 1 Aug 1864 to 1 Aug 1866, were used to raise revenue for the Civil War. The 2 cent stamp on the reverse of this photograph of an unknown woman in the Elting album tells us this photograph was taken around the end of the Civil War and cost less than 25 cents. The chair in this photograph, called a "fringe chair" because of the fringe along the side arm, back and bottom skirt, was a standard prop for professional photographers of this era. It was patented in 1864. The back and the side arm could be raised and lowered allowing the photographer to pose his subjects in different positions. The photograph was taken by Slee Brothers in Poughkeepsie. As noted in their advertisement, one of the advantages of the newer technologies was the ability to make copes. The skylights were also important because other lighting options were limited. Some of the features of the Slee Brothers studio which are mentioned in their advertisement can be seen is this recreation of a photographic studio. This is a stereoptic view of a Civil War encampment in Poughkeepsie also taken by Slee Brothers. If you'd like to learn more about the history of photography, this an interesting article

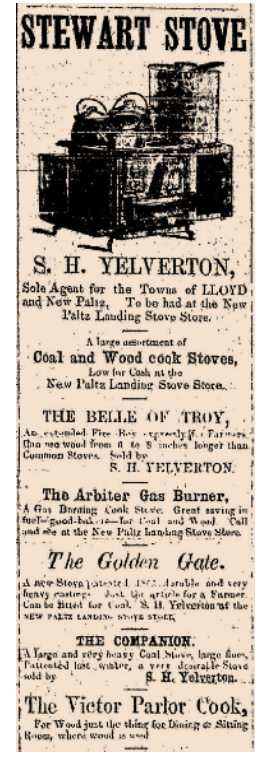

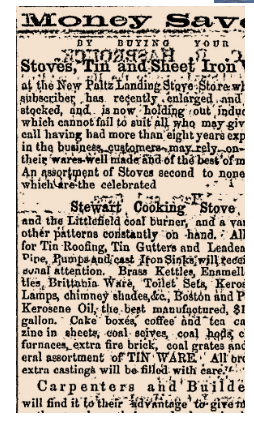

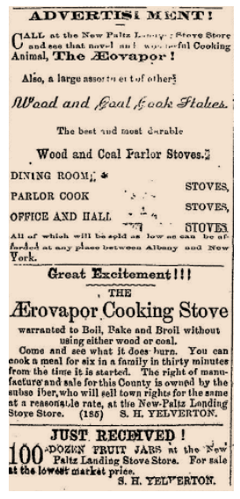

https://notquiteinfocus.com/2014/10/16/a-brief-history-of-photography-part-11-early-portrait-photography/  More than a century before Lowe's opened their establishment in Highland, Stephen H. Yelverton's store in New Paltz Landing was supplying local homeowners with all the latest devices needed to improve their homes. The Yelverton name is familiar in Highland history. Before 1754, Anthony Yelverton built the oldest known house/store on the western shore of the Hudson, opposite Poughkeepsie, in one of the few places that allowed access to the river. It was located in the town of New Paltz, so the waterfront area became known as New Paltz Landing, a name that continued decades after the town of Lloyd was separated from New Paltz in 1845.  Anthony constructed mills and established a ferry which ran between Highland and Poughkeepsie. Anthony's son, Anthony, and grandson, Anthony, gradually sold off the businesses in New Paltz Landing by 1812. Various Yelvertons appear in the later censuses, but Stephen H. Yelverton first appears in the 1860 census as a "tinman" who, according to the census, was born in 1836 in Greene County. About 1858, he married Sarah M. Osborne and their first child, Alfred F., was baptized January 6, 1860 in Holy Trinity Church in Highland. A daughter, Jane,was born in 1862. According to this advertisement in the New Paltz Times on September 28, 1860, Stephen Yelverton had been in business for eight years. The ad mentions his tin-working skills and goes on to list all items an 1860 homeowner might require to make their life easier. (The 2021 winter storm and power outages are a reminder of a life without electricity, running water and central heat – standard living conditions for our ancestors). By April of 1862, Stephen Yelverton's business must have been thriving; he took out a full column advertisement in the New Paltz Times, featuring many models of cook stoves.  A three column advertisement in October 1862, features a fancier version of a stove for the parlor.  New technology, "the novel and wonderful Cooking Animal, the AEovapor" was advertised in December of 1864. Anthony Yelverton appears in the 1865 Agricultural census and then apparently drops out of sight. . An article published in the Hudson Daily-Star on December 13th of the year, explains his disappearance.

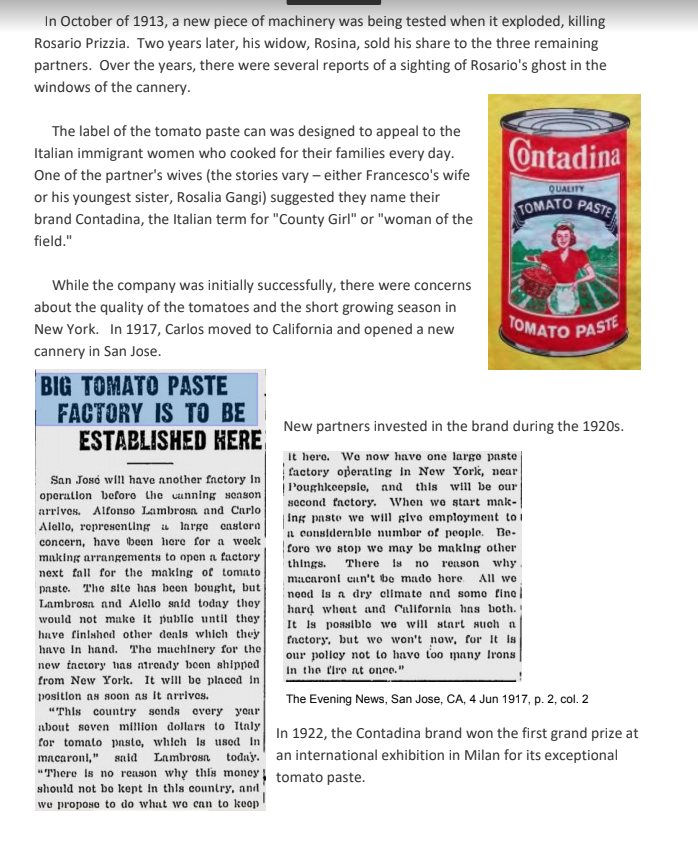

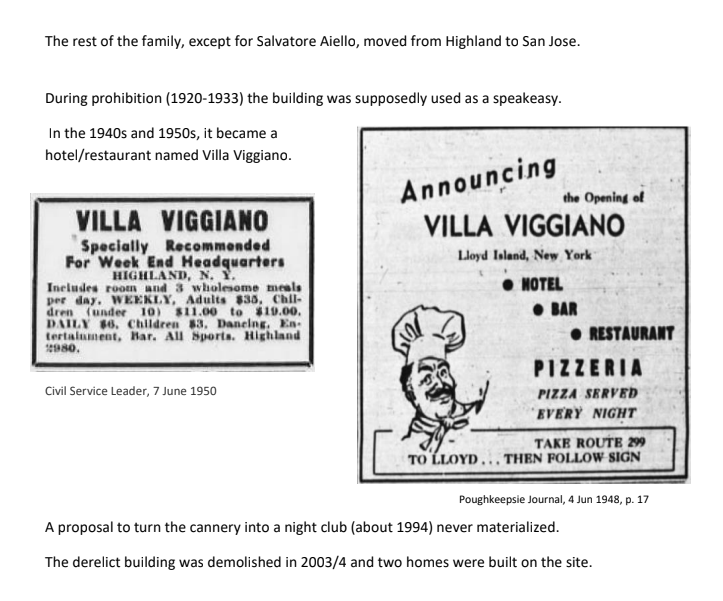

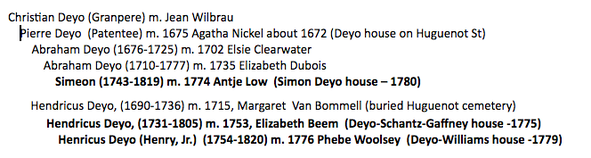

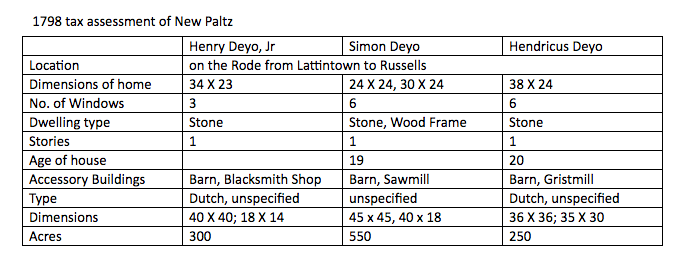

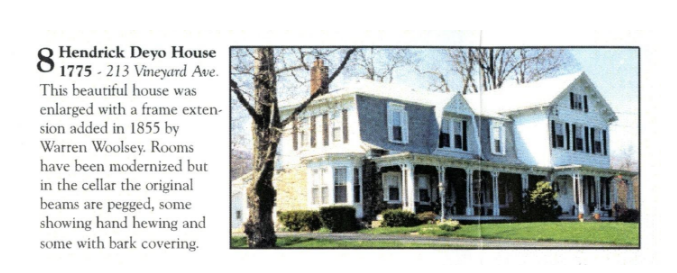

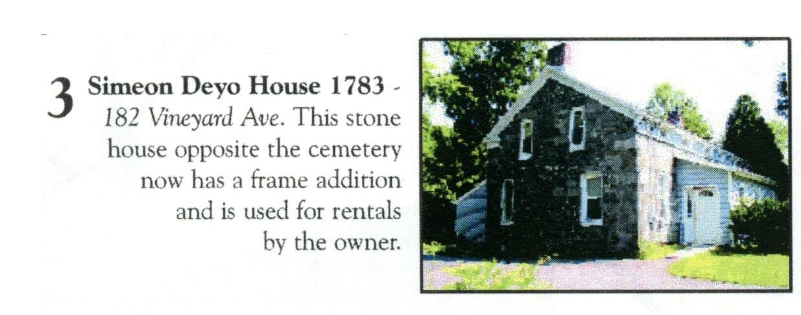

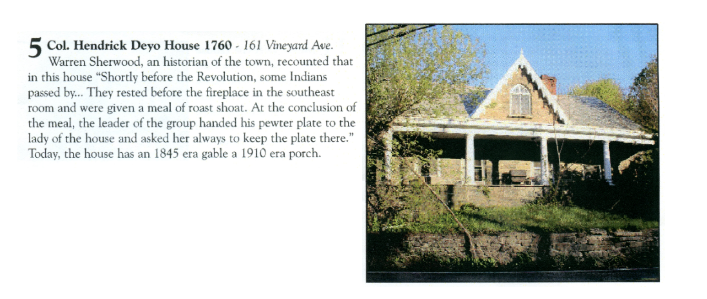

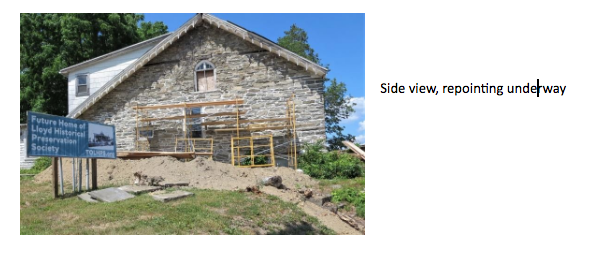

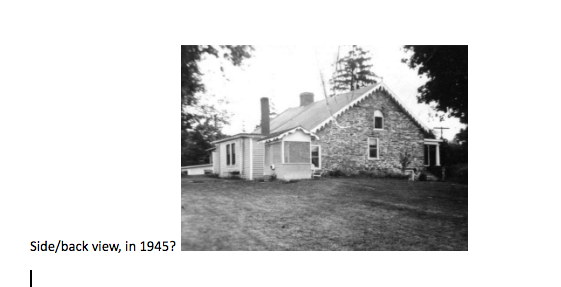

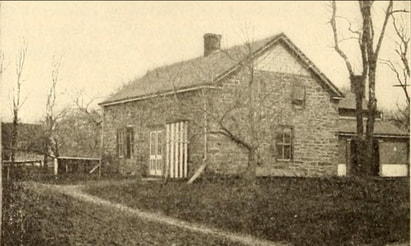

Perhaps he sorted things out…on July 20, 1871, the New Paltz Independent reported One of the treasures in the Historian's office is a beautiful brochure produced by one of our former Historians, Terri Scott. The "Self-guided Tour of Heritage Houses in Highland, New York" contains descriptions of three houses built by various Deyo's. I was curious how these Deyos might be related to each other and the original Deyo settlers of New Paltz. The Deyo family in Ulster County began with Christian Deyo. He was not one of the original twelve Patentees of New Paltz, but his son Pierre was a Patentee and his four daughters married Patentees. Christian was known (even in official deeds) as "Granpere" because he was literally the grandfather of the majority of children in early New Paltz. The Deyos of Highland descended from two of Pierre's sons, Abraham and Hendricus. The boys (and four other siblings) grew up in this house that Pierre built on Huguenot St.  Photo from Ralph LeFevre, History of New Paltz, p. 262  You maybe be more familiar with the way the house looks today, after a MAJOR remodel in 1894. As children, grandchildren and great grandchildren were added to the family, descendants moved out of the village of New Paltz to the surrounding areas. Three Deyo descendants, Simeon, Hendricus and Henry, Jr., built stone houses in Highland, on the road now known as Vineyard Ave. This diagram shows their place on the family tree: Henry Deyo, Jr. House - 1775It was later the home of three generations of town supervisors - Nathan Williams, his son, Winthrop Williams and his son, Nathan Williams.  Rear view of the house, circa 1945 Simon Deyo, Jr. House – 1779Hendricus Deyo House – 1775The house was acquired by Scenic Hudson in 2008 and conveyed to the Town of Lloyd Historical Preservation Society in 2015. Restoration work has begun. Donations can be made here for continuing restoration to be made to the building, which will be a public museum and library A wealth of information about the history of this house can be found in Deyo-Dubois - Existing Conditions Report, available in the Town Historian's office.

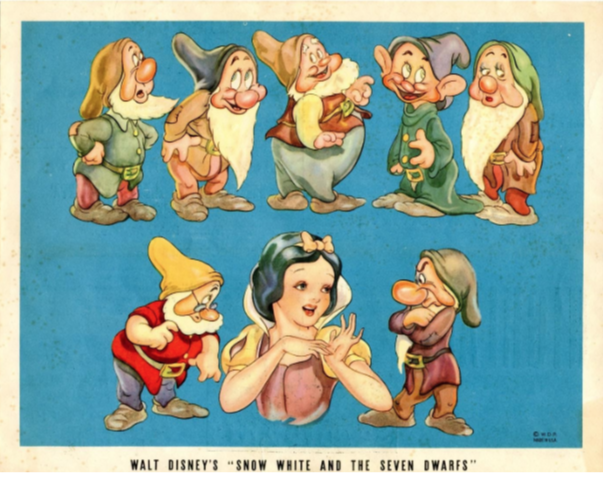

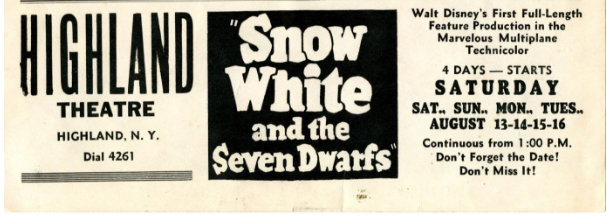

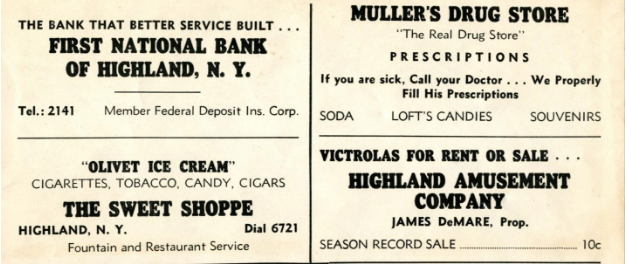

Town of Lloyd Historian Joan de Vries Kelley We recently received a wonderful movie poster from Fred and Anne Schühle. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" was the first full-length animated film released by Walt Disney; it made its U.S. debut in Feb. of 1938. The reverse side of the poster announces its showing in the Highland later that year. Where did you go after the movie? Maybe to the soda bar at Muller's Drug Store or The Sweet Shop. While you were enjoying your ice cream soda or a milk shake, you could like listen to your favorite tunes on one of the juke boxes supplied by James DeMare's Highland Amusement Company.  The first theater in this location was established by Milo Gregory in 1914. It passed through several owners until it was purchased by Walter Seaman in 1922. The theater, known as the Cameo Theatre, was severely damaged by fire in Nov. 2, 1934. The renovation of the theatre took three months and cost $20,000. The Marlboro Record reported on Feb. 1, 1935, "the designers and craftsmen have been engaged in transforming the old structure into a cinema palace which would do credit to a city many times the size of Highland." The seating capacity was 407; the walls and ceilings were covered with celotex, the latest technology which was washable, as well as acoustically superior. "Chrome pilasters at regular intervals on the side walls and chrome moulding on the ceiling add much to the appearance." A beaded curtain of silver completed the décor. Two new projection machines and the Western Electric sound equipment were considered the "same as used in practically all the most famous theaters of the county." The theater was renamed the "Highland Theatre." A large canopy and neon sign were just installed when "spectators were much thrilled Wednesday when the brick façade of the Cameo Theater buckled dangerously under the weight" of the new addition. It was quickly lowered and reinforced. In 1938, the theatre was sold to Frances Vincent Walsh. When he died in 1943, his children continued to run the theater. It was sold in 1954 and passed through several owners until it was purchased in 1969 and converted to the "Highland Art Cinema" which showed adult films. It closed in 1985 and was destroyed by a fire in 1987. The site is now a parking lot next to Sal's.

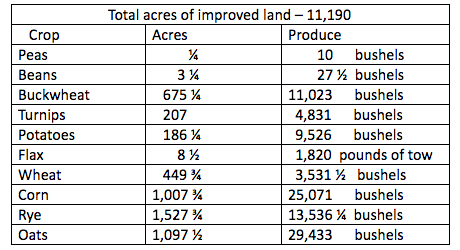

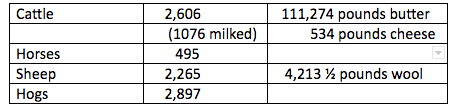

Town of Lloyd Historian Joan de Vries Kelley  When our new nation was formed at the end of the Revolutionary War, New York State decided some governance was best done at the local level. In 1788, they divided counties into towns which were primarily responsible for keeping the peace and maintaining roads. Lloyd was not one of the original towns; it was part of the Town of New Paltz. New Paltz stretched from the Shawangunk Mountains to the Hudson River, an area of about 40,000 acres. At first, the area along the Hudson was sparsely populated, but as its population grew, governing such a large area became difficult – the fastest form of transportation was a horse and post offices were few and far between. Residents of the remote parts of New Paltz felt they were being neglected. Finally, on Apr 15, 1845, New York State created a new town from the eastern part of New Paltz. They declared the town would be named Lloyd, and its first town meeting would be held on the first Tuesday of May at the house of Lyman Halstead. The town's residents assembled on May 6 in the ballroom of Lyman Halstead's hotel. The "ballroom" was the room over the stables – perhaps "Dance Hall" would have been a more accurate description. The men (only men with property worth more than $250 were allowed to vote) elected the first town supervisor, three justices of the peace, a town clerk, a superintendent of schools, a highway commissioner, an overseer of the poor, and , of course, a tax collector. Apparently quite a celebration ensued after the meeting. Thanks to a summary of the 1845 census, we know a bit about the new town. The population of 2035 consisted of 1036 men and 999 women. There were 239 married women under the age of 45 and 187 unmarried females between the ages of 16 and 45. (As historian Sherwood remarked "Quite a range of old maids" note – he never married). In the year preceding the census, there were 19 marriages, 77 births, and 24 deaths. 212 Men were subject to military service and 464 were entitled to vote. There was 1 pauper, 2 deaf and dumb, 3 blind, 1 idiot and no lunatics. There were 10 merchants, 6 manufacturers, 126 mechanics, 1 attorney and 1 physician but most of the men, 312, were farmers. Here's is a summary of what they produced. Much of the unreported acreage was probably orchards; fruit production was a big part of the economy. And, of course, there were animals. Much of this produce was shipped to New York City, as reported in this article "Receipts of Produce by North River Boats" published in New York City on Apr. 29, 1847. Bark Berkshire, L. Elting, from New Paltz – 2500 bushels corn 200 bbls rye flour 50 bales hay 80 tubs butter 20,000 eggs 180 calves 30 bbls apples to the captain. The women also contributed to agricultural output by spinning and weaving 1611 ¾ yards of cloth, 1928 yards of flannel and wool, and 485 ½ yards of linen. Supporting the farms were 8 gristmills, 3 saw mills, 1 carding machine, 1 woolen factory, 7 tanneries and no distilleries. The town included 5 inns, 9 retail stores, 2 Presbyterian churches (the old meeting house had not yet been removed) and 1 Methodist church. At the time of the census, no ministers were recorded, so the churches must have been temporarily vacant. There were 9 district schools for 306 pupils; the average daily attendance was 174. As Sherwood summarized "Altogether the Town was rural, productive and didn't care too much for "book larnin." But it was a good town full of the promise of good things to come." Town of Lloyd Historian Joan de Vries Kelley |

Archives

November 2021

Categories |

Location |

|